Conrad Buff - The Other-Worldness of the West

Sunday, October 2, 2011 at 10:37PM Tweet

Sunday, October 2, 2011 at 10:37PM Tweet by Donna Poulton

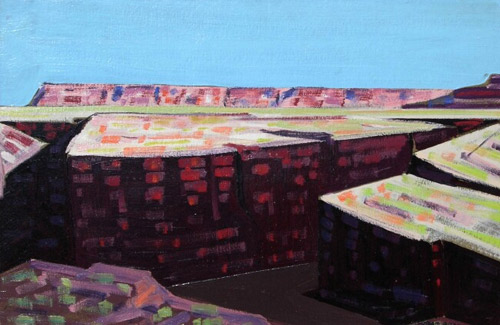

Canyonland. Credit: Donna Poulton and Vern Swanson Painters of Utah’s Canyons and Deserts

Canyonland. Credit: Donna Poulton and Vern Swanson Painters of Utah’s Canyons and Deserts

There are few artists of the southwest whose technique is as expressive or singular as that of Conrad Buff (1886-1975). His Modern interpretation of the southwest, using high-keyed architectural compositions and broken color patterns to distinguish the desert landscape, is unrivaled. Born and raised in Switzerland, Buff moved to Los Angeles in his mid-twenties where he studied art under a number of instructors, but his work with Edgar Payne seems to have been a pivotal point in guiding his art career, especially in mural work.

Landscape with Trees. Credit: Donna Poulton and Vern Swanson Painters of Utah’s Canyons and Deserts

Landscape with Trees. Credit: Donna Poulton and Vern Swanson Painters of Utah’s Canyons and Deserts

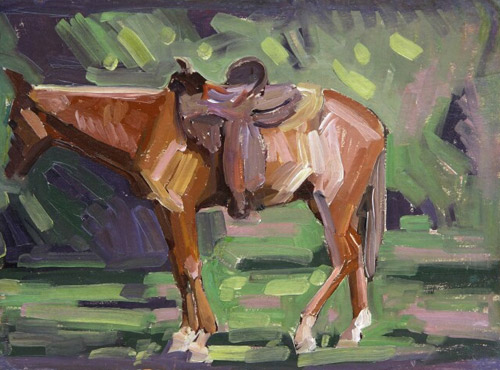

Horse. Credit: SternFineArts.com

Horse. Credit: SternFineArts.com

In 1923, Conrad Buff and his wife, Mary, made the first of many trips to the then relatively undiscovered Zion National Park. Buff wrote that as they drove to Zion “The air got clearer and clearer and the landscape was as fantastic as it was beautiful. Always the same varied pattern of hills, the same foreground with the sagebrush, but the air was so clear that the design of the hills stood out against the deep blue sky which has always fascinated me and still does—the deep blue sky and the mountains and hills against it.”

Canyon Wall, Zion National Park. Credit: Donna Poulton and Vern Swanson Painters of Utah’s Canyons and Deserts

Canyon Wall, Zion National Park. Credit: Donna Poulton and Vern Swanson Painters of Utah’s Canyons and Deserts

In the late 1920s Buff was commissioned to paint mural decorations for a social hall in Huntington Park, California. After seeing other Utah landscapes and work related to the mural project at an exhibit at the Los Angeles Museum, Los Angeles art critic Merle Armitage wrote, “Conrad Buff comprehends the enormity of the West. More than that, he adds thereto a discernment of the stylized and conventionalized forms in which the West abounds. Not one artist in a hundred grasps the significance of the West’s dynamic forms.”

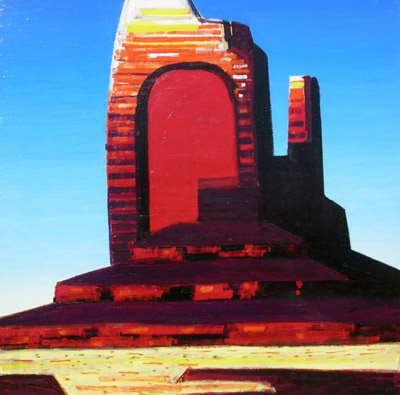

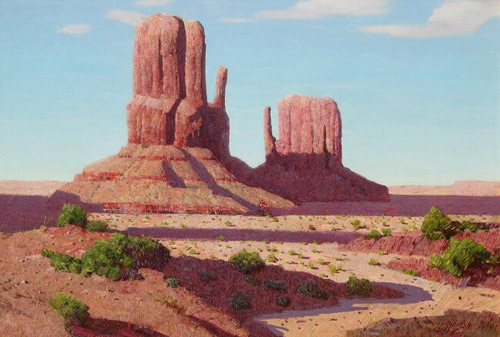

Monument Valley. Credit: SternFineArts.com

Monument Valley. Credit: SternFineArts.com

An exhibition at the Ilsley Gallery in Los Angeles showcased some of Buff’s Utah scenes, and a large Zion scene especially interested one exhibition visitor—Maynard Dixon. Will South wrote that, “Immediately, there began a friendship which lasted as long as Maynard Dixon lived….[Dixon] was impressed by the style of the young Swiss and also by the locale of some of his paintings.” South goes on to note that “According to Buff, Dixon was quite taken with a view of Zion National Park and had to ask its location because he had never been there on his own many travels of the West. Two months later, in June 1933, Dixon headed out to Zion in the company of his wife, photographer Dorothea Lange (1895-1965)…”

Monument Valley. Credit: SternFineArts.com

Monument Valley. Credit: SternFineArts.com

During the Depression Buff worked briefly for the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP). Art critic Arthur Millier wrote, “…resting on Mr. Buff’s exploration, one can visualize a future school of painter, to whom he will have discovered the other-worldness of a region in which it is not uncommon to see, one behind another, red, white, black and blue peaks. What at first seems to be his personal colorations turn out to be typical of the desert slope of mountains."

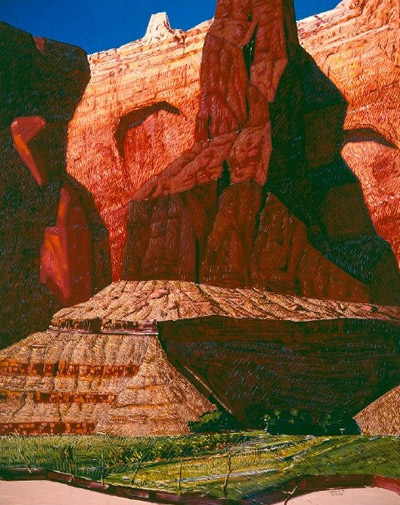

Canyon de Chelly. Credit: SternFineArts.com

Canyon de Chelly. Credit: SternFineArts.com

Canyon Land (see above) depicts a large bluff surrounded by the waterway that has, over the millennia, cut its large rectangular profile and left it standing alone as an island. The painting is unusually monochromatic for Buff, and his identifiable short brushstrokes and cross hatching are absent. It suggests the silence and isolation of the eons and the weight of time. Ed Ainsworth reported that Buff “repeatedly journeyed to the country known as the Wayne Wonderland on the Fremont River…sometimes with his wife and the Dixons.”

Deep Canyon. Credit: SternFineArts.com

Deep Canyon. Credit: SternFineArts.com

Will South has suggested that it was his German accent, but whatever the reason, Conrad Buff spent much of his time in southern Utah during the War years. From this period came an outpouring of paintings and an evolution in his composition and method. Since most of his paintings are undated and untitled it is difficult to ascertain exactly when and where the work was done. Buff observed that:

Landscape painting has been my favorite thing practically all my life. But I found out that the way that I saw landscape, especially the western landscape that I was so much in love with, wasn’t the way the public saw it. I just couldn’t get interested in the verbenas and the sunsets. I kept on painting these magnificent forms that I saw and that I was interested in, and I tried to get the magnificent blues that we saw on the desert, which wasn’t so easy to harmonize with the rest of the landscape. And especially the wild country in Utah.

Utah Mesa. Credit: SternFineArts.com

Utah Mesa. Credit: SternFineArts.com

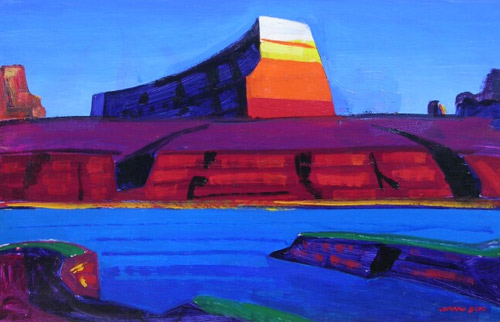

Throughout the later 1950s and 60s, the perspective in Buff’s paintings comes down to eye level. Landscapes that had been set at dizzying heights to illustrate the stature and depth of desert monoliths is replaced by scenes set at ground level. But with the change in altitude came attendant explorations with plasticity. The sky remained his signature blue, largely unbroken by texture or line, but the foreground elements were applied with thicker impasto and longer brush strokes. The impression of light was achieved by the application of pure color rather than blending on the palette.

Lake Powell, Utah. Credit: SternFineArts.com

Lake Powell, Utah. Credit: SternFineArts.com

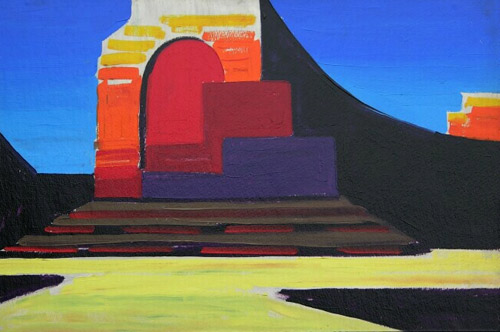

Buff’s mature desert series advanced further in the 1970s to expressive primary colors, flattened planes and architectural edifices recognizable only because they are iconographic emblems of the desert. In these paintings, the landscape is an object - it has been stripped of the painterly devices of thick impasto, cross-hatching and the neo-impressionistic techniques of broken color. Nature has been reduced to minimal form and pure color, but in doing so Buff has established his own unrivaled vision of the West and nothing of its essence has been lost.

Untitled, Southern Utah. Credit: Donna Poulton and Vern Swanson Painters of Utah’s Canyons and Deserts

Untitled, Southern Utah. Credit: Donna Poulton and Vern Swanson Painters of Utah’s Canyons and Deserts

Reader Comments (1)

So great to see these paintings by Conrad Buff. The observation that he emphasized the geometric forms and was not at all interested in the flora on the desert floor was something I have never thought much about. His work became more and more abstract as time went on, making powerful statements and gave us all a new way of looking at the mesas and monolithic rock formations that have emerged over time in all of the southwestern deserts. Thanks for sharing these and for your very insightful analysis!