Vanishing Point: America's Great Frontier

Wednesday, May 11, 2011 at 10:20PM Tweet

Wednesday, May 11, 2011 at 10:20PM Tweet By Jim Poulton

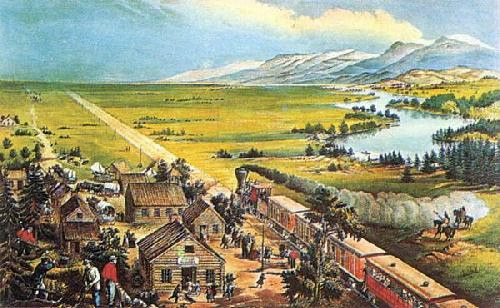

Across the Continent, Currier & Ives. Credit: EasyArt.com

Across the Continent, Currier & Ives. Credit: EasyArt.com

In 1868 the lithography firm of Currier and Ives produced a print illustrating a railroad heading into the American West. The print captured the spirit of the times. It was still the early decades of westward expansion and the American people persisted in seeing the west as a near-infinite frontier with abundant resources. The Currier and Ives print simply put into pictorial form the image most people already had of the western half of the country.

Not everyone, though, saw the west this way. In 1890, the U.S. Bureau of the Census declared that the frontier no longer existed. The Bureau had defined a frontier as having no more than two people per square mile. The west, to just about everyone's disappointment, had surpassed that criterion.

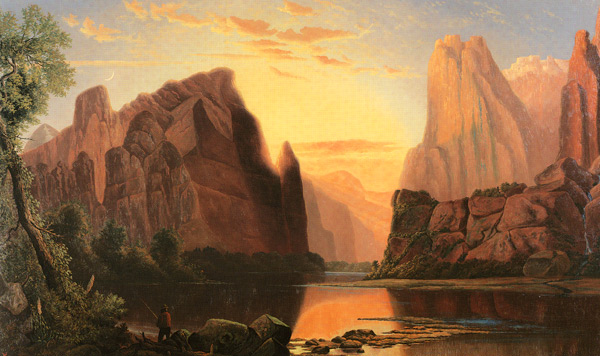

In the Mountains, Albert Bierstadt. Credit: AlbertBierstadt.org

In the Mountains, Albert Bierstadt. Credit: AlbertBierstadt.org

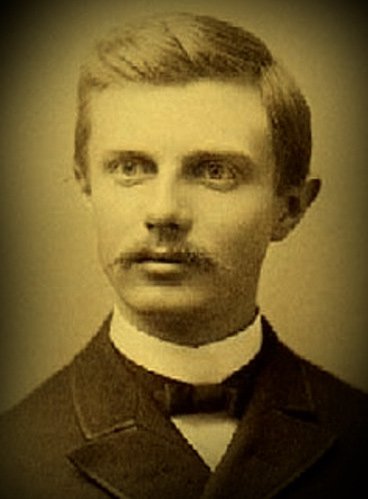

Reaction to the Bureau's declaration was swift, especially among America's intelligentsia. In 1893, Frederick Jackson Turner, a professor from the University of Wisconsin, gave a speech that was to become one of the most influential pieces of American writing in the 19th century. In it, Turner mourned the passing of the frontier, and heralded all that it had done for America.

Frederick Jackson Turner. Credit: Illinois Mathematics & Science Academy

Frederick Jackson Turner. Credit: Illinois Mathematics & Science Academy

“From the conditions of frontier life came intellectual traits of profound importance. The works of travelers along each frontier from colonial days onward describe certain common traits, and these traits have, while softening down, still persisted as survivals in the place of their origin, even when a higher social organization succeeded. The result is that, to the frontier, the American intellect owes its striking characteristics. That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness, that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients, that masterful grasp of material things, lacking in the artistic but powerful to effect great ends, that restless, nervous energy, that dominant individualism, working for good and for evil, and withal that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom -- these are traits of the frontier, or traits called out elsewhere because of the existence of the frontier. …

What the Mediterranean Sea was to the Greeks, breaking the bond of custom, offering new experiences, calling out new institutions and activities, that, and more, the ever retreating frontier has been to the United States directly, and to the nations of Europe more remotely. And now, four centuries from the discovery of America, at the end of a hundred years of life under the Constitution, the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history.”

- Frederick Jackson Turner, The Significance of the Frontier in American History

Children of the Mountain, Thomas Moran. Credit: Wikimedia

Children of the Mountain, Thomas Moran. Credit: Wikimedia